If we go away and leave a piece of land alone, it often "comes back" to something resembling its original state. Although not every ecosystem is sufficiently resilient, we have such a system here at Varner-Hogg Plantation. This land has undergone devastating environmental degradation ... yet it has largely recovered. Of course, it will never recover fully -- invasive species like fire ants and Chinese Tallow will always be around. Still, recovery is evident throughout the park.

Our story begins in 1821. Why 1821? That's the year when Mexico won its independence from Spain. The new Mexican government wanted to encourage settlement ... in particular, it wanted to encourage settlement in the northeastern state of Coahuila & Tejas -- now Texas. As part of this effort, it offered "Empresario Land Grants" to individuals willing to establish settlements. And yes, that's the correct spelling of "Empresario" in modern Spanish.

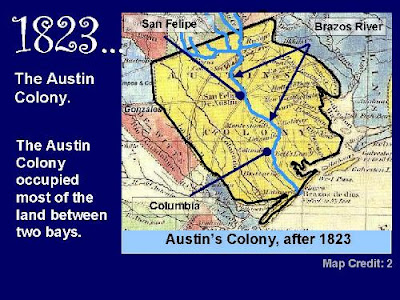

Moses Austin, a U.S. citizen, received one of these grants -- it authorized him to settle 300 families. Moses Austin died a few months later, leaving the job to his son, Stephen F. Austin. Stephen Austin selected the area shown here, along the Gulf Coast between Galveston Bay and Matagorda Bay.

By 1823 ...

... it was known as the "Austin Colony," with a capital of sorts at "San Felipe de Austin" -- now San Felipe. It occupied the land between Matagorda Bay and Galveston Bay, and extended several miles inland.

Down here [point to box], we see Columbia (now West Columbia) and Bell's Landing (now East Columbia). And just north of Columbia ...

. . . is a parcel of land taken up by one of those 300 settlers, a man named Martin Varner. It's on west bank of the Brazos River.

This is a copy of a map made in 1947 by the Texas Land Office. A copy of the complete map is on exhibit at the Brazoria County Historical Museum in Angleton.

Where is it geographically?

Here we see Varner's grant overlaid on a modern map. It's a huge parcel of land -- one Spanish "league" -- over 4000 acres -- almost seven square miles.

The Varner Hogg Plantation Historic Site is just a small piece of the original grant -- most of the rest of the land is now in private hands. Practically the entire City of Columbia Lakes is inside the grant.

The land over here [point] and up here [point] is owned by private landowners.

And where is it ecologically?

Here's Varner's grant overlaid on a map of the Columbia Bottomlands that I (Neal) filched from the Gulf Coast Bird Observatory's website. Note that most of the site is hardwood forest, but there's a bit of coastal prairie up here [northwest corner].

If Martin Varner wanted access to water, he picked a good site. Here's the Brazos River. And this is Varner Creek [point]. We don't know if Varner called it that, but that's what we call it today.

Martin Varner cleared land for agriculture, probably starting in that northwest corner of coastal prairie. He planted corn and sugar cane, and raised livestock.

He also built a rum distillery. Those of you who visited the Plantation site last week probably remember the story about the famous bottle of rum that Varner sent to Stephen Austin. Austin credited Varner with making the first "ardent spirits" in the colony.

The sugar cane plant shown here is growing near the Varner Hogg visitors' center, in a little garden of historic plants maintained by one of our friends in the Master Gardeners program.

Varner only stayed for ten years -- he had to stay that long to satisfy the terms of his agreement with Stephen Austin. As soon as his ten-year commitment ended, he sold his grant to Columbus Patton.

Patton had a large family and several slaves. Together, they cleared the rest of the land and established a large sugar plantation. They also built a "sugar house" to extract the sugar from the cane. This is one of the sugar kettles used to concentrate sugar syrup.

The sugar house was destroyed by the 1900 hurricane, but the brick foundation is still visible today. During the cane harvest season, the sugar house ran 24 hours a day. Sugar was obtained from sugar cane by extracting juices from the center of the cane, and concentrating it in a series of evaporation kettles.

During the 1840s, Patton owned as many as 80 slaves, all of whom must have worked long hours during the cane harvest season.

Patton also constructed a home for his family -- the Plantation House. The walls are constructed of bricks made by slaves from local clay. The home is still standing today, although it's undergone extensive renovations since Patton's day.

This is the earliest known photograph of the Plantation House, although it was taken in 1903, long after Patton sold the property.

A lot of things happened during the latter half of the 19th century...

- Columbus Patton died in 1856, and his family sold the property.

- During the next several years, the property changed hands several times.

- The Republic of Texas became the State of Texas in 1856; it then seceded to join the Confederate States of America during the Civil War, and was finally readmitted to the United States in 1870.

- James Stephen Hogg served as Texas Governor for four years.

- The storm of 1900 -- apparently a hurricane/tornado combination -- destroyed the Sugar House, the slave quarters, and several other buildings, but it missed the Plantation House.

James Stephen Hogg served as governor of Texas from 1891 to 1895. After he left office, he established a law practice in Houston, and purchased the Plantation as sort of a weekend retreat.

Hogg suspected that oil might lie hidden under the property. He died in 1906, but his will specified that the property could not be sold for 15 years.

Governor Hogg's suspicions were correct: oil was indeed discovered on the property. His four children became quite rich.

But the property must have been an environmental disaster by the end of the oil era. In this historic photo, the Plantation House is completely surrounded by oil derricks. [Point out Plantation House.]

The electric drive mechanism for one of the wells -- named "Miss Ima #4" in honor of Governor Hogg's daughter Ima -- can be seen on the site today.

After Hogg's death, his children continued to use the home. His daughter Ima -- affectionately known as "Miss Ima" -- renovated the home, adding modern conveniences but retaining period furnishings. The exterior you see today is stucco, applied over the old bricks which were deteriorating.

In 1958, Miss Ima donated the 53-acre parcel containing to the Plantation House to the State of Texas. The property is now operated by Texas Parks & Wildlife as the Varner-Hogg Plantation State Historic Site.

Our Master Naturalists Team 2 visited the site in October to learn about the Plantation, and to conduct a species inventory.

What did we find?

We found a "planted landscape": lawns . . . fences . . . ornamental plantings around the Plantation House arranged for shade or interest.

By the way, notice the color of the paint on the roof of this breezeway. Anybody know why that is?

Answer: It's painted to look like the sky so mud dauber wasps don't build nests under the roof.

We encountered landscape plantings around several buildings. Note the sugar kettle recycled as a lily pond.

East of the house, we found a banana tree. Note the bud [left image] and the fruit [right image].

West of the house, we encountered a Ginkgo biloba -- that's about as non-native as you can get. Note the shape of the leaf: two lobes = biloba.

Of course, many of the plants we encountered in the planted landscape were indeed natives. . .

. . . broad expanses of mowed lawns . . .

. . . interspersed with isolated trees and picnic areas . . .

. . . an old pecan orchard . . .

. . . and an old grape arbor. . .

We encountered several non-native invasive species that had escaped from cultivation.

Chinese Tallow Tree. . .

. . . and the Golden Rain Tree.

Outside the park -- but still within the boundaries of Varner's original grant -- we noted the typical rural-Texas landscape: agriculture and livestock. Just outside the park's eastern boundary lies the Columbia Lakes golf course.

Still, at every turn, we noticed resilience: "the ability of a natural ecosystem to return to its original state after disturbance."

Despite the severe environmental disruptions of the past 175 years, we found many native plants -- and animals -- carrying on.

In spite of frequent mowing, the native Shore Milkweed managed to poke up through the non-native grass.

The grand old live oaks, and the Resurrection Ferns they support, seem to have ignored the entire 175-year disaster.

The Balloon Vine -- an opportunistic native that takes advantage of open space. The seed reminds us of the Chinese "Yin-Yang" symbol.

We found several examples of new-growth woodland species . . .

. . . Slash pine . . .

. . . Hackberry, also called Sugarberry . . .

. . . Sweetgum . . .

. . . American Sycamore, also called American Planetree . . .

. . . Texas Persimmon.

And this curiosity -- a native Cedar Elm trunk growing completely around a native Hackberry.

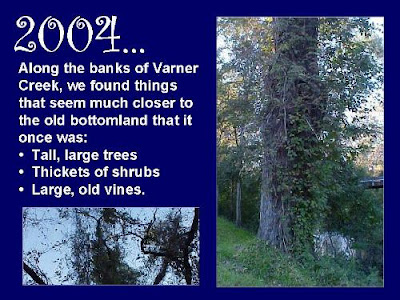

When we went prowling along the banks of Varner Creek, we found a situation that seems much closer to the way the undisturbed Columbia Bottomland must have looked:

- large, tall trees.

- Thickets of shrubs.

- Large, old, tangled vines.

Tangled vines . . . Including a couple that look like knot-tying exercises.

Thickets of trees, including one so weighted down with vines that it apparently broke in half.

Animals can be resilient, too.

Some members of the animal kingdom have an easier time in recolonization. Birds and flying insects can spread easily for some distance, once suitable conditions return. But others may take longer. We saw examples of both.

We visited the park very early one October morning to count bird species. At one point, a belted kingfisher zoomed under our bridge crossing over the creek. His rapid rattling call sounded like a machine gun.

Other members of the animal kingdom we noted a monarch butterfly and a skipper butterfly on frostweed.

The humid bottomlands along the creek banks were the only places where we encountered slow-moving or shy species like slugs or snakes. Of course, many species -- even fast-moving birds -- may need the natural bottomland as a place to feed, rest, or reproduce. We discovered this slug under a decaying log.

We discovered this Southern Copperhead skittering through forest litter. Mickey Dufilho amazed us all by her bravery, as she pursued it, camera in hand.

Fortunately for our photographers, the Golden-silk spider posed very calmly.

And that ends the brief photographic list of the species we saw. But we saw (or heard) many more. There's a complete species list in your handout on pages 9 and 10.

Resilience: "the ability of a natural ecosystem to return to its original state after disturbance."

The land comes back.

Questions?